Transgender people have never had a great relationship with medical care. Most trans people have stories about being mistreated while obtaining medical care — not just for trans-related healthcare, but also for general healthcare. It’s not unusual to be refused treatment by transphobic doctors, to be misgendered and dead-named by providers, to experience the biases the medical profession has against sex workers (whether or not we’re a sex worker), and to be subject to assumptions (without necessarily any evidence) about what gender we really are.

Sometimes the problem is intrinsic in the way medicine sees trans bodies and the research that enlightens the medical world.

Reference Ranges

Some medical tests have different reference ranges, based on sex. For instance, we know that hemoglobin and creatinine levels in blood differ by sex (cis men tend to have more hemoglobin than cis women; they also often have more creatinine in their blood). We know men tend to have less body fat and more muscle than women. And, relevant to this article, we know spirometry test (this measures amount and speed of air inhaled/exhaled, to measure some parts of lung function) results differ between healthy men and healthy women. These ranges are generally developed based on what is normally observed within a population of healthy people.

A content note for this article: I’m not going to discuss the emotional and psychological impacts of treating us as someone we’re not, although that is important in itself. I’ll also add that I’m not a doctor or otherwise qualified to practice medicine, so please don’t take any of this as medical advice.

What happens when a trans person sees the doctor?

Which range does the doctor use?

An Example — Hemoglobin

We know sex hormones have a significant impact on a lot of bodily systems, so for some medical care, it’s important to consider the sex hormones in a person’s body (their hormonal sex). For instance, testosterone increases red blood cell count (and thus also hemoglobin, which is found in red blood cells). So a trans woman with suppressed testosterone, either because her gonads have been removed or because she’s on hormone replacement therapy (HRT), would be expected to have a lower red blood cell count (and hemoglobin level) than a cis man. Likewise, a trans man with typical cis male levels of testosterone would be expected to have a higher red blood cell count (and, thus, higher hemoglobin level) than cis women.

Sure enough: That’s what the research by Kaiser Permanente Washington and the University of Iowa found. For someone that is on feminizing hormones, use the same range you would use for cis women. For someone that is on masculinizing hormones, use the same range you would for cis men.

Gender Assumptions in Medicine

Yet, my personal experience is that most doctors and medical researchers assume we should be treated, medically, according to our birth sex when interpreting medical tests. Yet most physicians and medical researchers have had little training in transgender medicine. Indeed, they are acting on a bias that doesn’t have evidence. The bias, in this case, is that a trans person’s “true” sex, medically, is the one they were assigned at birth.

Transgender Spirometry

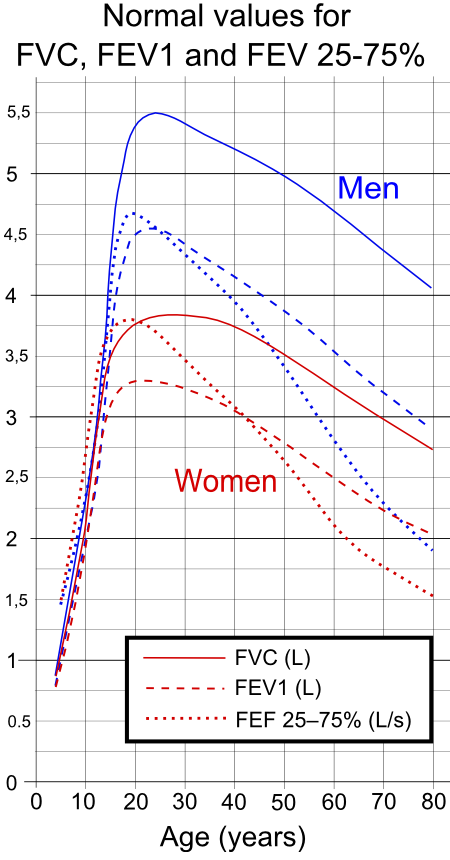

In spirometry, several aspects of lung function are measured by having a person blow (exhale) into a special machine. The first measure, FVC (Forced Vital Capacity), is the total amount of air you can exhale after breathing in as deeply as possible (in however long it takes you to exhale this amount of air). If this is too low, it indicates something is restricting your ability to breathe, which is obviously a significant medical issue.

Another measure, FEV1 (Forced Expiratory Volume in one second), is how much air you can exhale in one second. If it takes you a long time to exhale, your FEV1 would be lower than your FVC. The FEV1 and FVC are compared — how much of your total possible exhaled air can be exhaled in one second? Ideally, this number is high. A low number could indicate an airway obstruction.

But of course all this depends on “What is normal for FVC and FEV1?” It turns out that there are at least two main factors used to compute what these values should be: sex and age.

If we were to try to apply these ranges to transgender people, the next question would be, “How do various transgender treatments likely impact these ranges?” To determine that, we would need to know why the male and female ranges are so different. So, why are they different?

One major factor is that men are bigger than women, on average. Thus men have bigger lungs than women, and bigger lungs will inhale and exhale more air. And sure enough, there are calculators that take into account this difference, by looking at height. A 5’2″ man would be expected to be able to exhale less than a 6’5″ man. See the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s Spirometry Reference Value Calculator to play with this on your own.

Race and Spirometry — A Bias? Racism?

One thing you’ll notice on the calculator is that the calculator asks for race, and computes lower FVC and FEV1 levels for blacks than for whites. The research this is based on may not be as straightforward as we would like in medicine, however, with a history of racial assumptions that do not consider social class or other intersectionality. In other words, these racial corrections may be racist. An article by Lundy Braun in the Canadian Journal of Respiratory Therapy, Race, ethnicity and lung function: A brief history, explores this in more detail. The implications of racism in spirometry, if present, are significant: we might be failing to recognize a significant health concern in a large group of people, that exists because of the intersection of race and class.

If racism might be a contributing factor to spirometry reference ranges, what other biases might exist?

Back to Physical Size

Going back to physical size — using the NIOSH calculator, we quickly discover the algorithm differentiates men and women, even if we enter the same height for both. Women are expected to have lower FVC and FEV1 levels for a given height. Why?

Much of it may be due to lung size, rib cage configuration, and diaphragm placement (see this article). These all combine to reduce the amount of air that a cis woman would be able to exhale.

So, this seems straightforward, right? Trans men should be treated like cis women, trans women should be treated like cis men, at least when interpreting spirometry results, right? Do we actually know that?

Importantly, do these physical dimensions change if someone is on puberty blockers from a young age, and then starts hormone replacement therapy (HRT), only going through the puberty of their gender? Maybe the ranges should be different for early- vs. late- transitioners who used HRT. These are still open questions.

Impact of Hormones on Spirometry

There may be more factors at play than physical size. As just one example, the strength of muscles involved in exhalation may impact spirometry values. Could they be impacted by hormones? The short answer is we don’t seem to know, but some research does show there may be a relationship between poor spirometry results and low testosterone in men. This isn’t enough to show a cause-effect relationship, nor did the study mentioned above look at healthy patients, which would be essential to determine any possible relationship.

This study, which found a positive association between HRT and respiratory health, examined elderly (and thus post-menopausal) women and looked at lung function. It concluded, in part, “Women who currently used HRT were less likely to have airway obstruction, even after controlling for variables known to influence pulmonary function”. Again, like the study cited above for testosterone, this does not prove a causal link, and is just the start of research on this subject — much more has to be done to study it.

That said, we know that trans people may use hormone replacement therapy (either masculinizing or feminizing), and teasing out the impact of hormones would seem to be important to determine the proper spirometry reference values for trans people.

So Has Anyone Studied Transgender Spirometry?

The short answer: no.

The longer answer: there are a couple articles that claim conclusions about this. One is a single-patient case study on a trans woman. While case studies are interesting, and they suggest directions for research, it’s hard to draw conclusions from a single case.

The other article studied more people — 160 to be exact. And this study, unlike a case study, had an experimental design (I.E. comparing a control to a non-control group).

What Does The Transgender Spirometry Study Say?

In The Impact of Using Non-Birth Sex on the Interpretation of Spirometry Data in Subjects With Air-Flow Obstruction (Haynes 2018), the researchers claim, in the conclusions presented in the abstract:

In transgender subjects with air-flow obstruction, using non-birth sex to calculate predicted spirometry values may have a significant impact on test interpretation and place these patients at risk for misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

So, how did they determine this? Did they compare trans people with cis people, and determine that the trans people should use the reference range assigned at birth?

NO.

They looked at data in a publicly available spirometry dataset on men and women. They selected 80 men and 80 women with air-flow obstruction from that dataset. As the authors of the study say, when discussing limitations, “we only examined adult subjects who presumably did not receive gender-guided hormone therapy.”

So, we came to a stunning conclusion: trans people should be treated according to their “birth sex” rather than their current gender, when interpreting spirometry — and we came to this conclusion without studying a single trans person.

When the study looked at these 80 men and 80 women, it ran the spirometry values against a predictive model that differentiates between men and women.

The research that created the predictive model is based on a sample of 23,572 people and showed a clear distinction between men and women, resulting in sex being incorporated into the equations. So from that original research we know that the ranges for men and women are different, and we can expect if you miscategorized cis people, there would be a different (and likely incorrect) interpretation of the results. You don’t need to do research to prove that — the original research already did that.

Nonetheless, that’s what the study on trans people (that did not include any trans people!) did. It ran the numbers of these 160 people both as white men and as white women, and observed that, yes, there were (as would be expected!) differences in the interpretation of the results based on the sex used to interpret the data. In some cases, these results could be significant. While I’m not sure that finding is actually interesting (I’m pretty sure we already knew this), it certainly doesn’t actually say anything about trans bodies. And I do have major ethical concerns with a study claiming to say something about trans people if that study doesn’t actually look at trans people!

Simply put, the conclusion does not logically follow from the findings. That doesn’t mean the conclusion is wrong — it very well may be right. But we don’t know if it is right or wrong based on this study.

Where to Go From Here?

The Haynes 2018 study discussed above does make a suggestion that is useful, and I hope is incorporated by medical device makers: if it turns out that birth sex is relevant for a given test, rather than expecting device operators to enter the birth sex in the user interface, instead ask for the person’s sex and provide a yes/no checkbox for “transgender”. When the transgender check box is selected, the other set of reference ranges could be used. This doesn’t solve the problem for non-binary people (presumably you would need to ask birth sex there), but it would reduce the chance of a birth sex flowing through the system and being seen/used by people who don’t need to know it. It would also provide a richer data set, because another possibility is that the transgender reference range for spirometry may be different than the non-transgender ranges completely, and may even be dependent upon such things as age at time of transition or length of time on HRT.

Regardless, we need more study about transgender bodies, to help figure out what a healthy transgender body looks like. And, ideally, that study would include actual transgender people.