If you are active in trans advocacy, you’ve seen various estimates for HIV in trans women: 42% (CDC)! 14% (Also CDC)! 24–28% (Baral, et. al.)!

I suspect none of these are right, and I think all over-estimate HIV prevalence among trans women. I recognize that’s a minority position — advocacy groups who depend on public health funding like to tout high numbers, as do HIV outreach organizations trying to convince trans women of the risk they may have of contracting HIV, much like the oft-cited, but wrong, 35-year-old estimate for the average life expectancy of Black trans women).

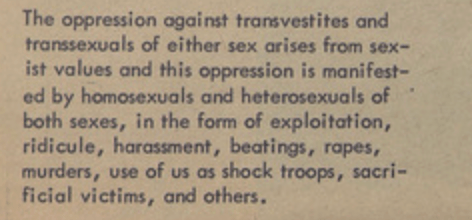

Certainly, Black trans women are at too-high of risk for violence (anyone who attends a US-based Transgender Day of Remembrance event will be struck by the number of Black trans people who are murdered each year — far outnumbering the white faces), and it’s a real problem. But we can make this point without incorrect statistics that also serve to discourage Black trans women from transitioning and living as who they are.

Likewise, the high HIV prevalence numbers can stigmatize trans people. Now, make no mistake: stigmatization of HIV positive people is a major problem and one we need to address head-on, and I’ll mention a few facts that some people might not know, that may reduce some fears about this virus:

- HIV positive people on appropriate medication often have well-controlled HIV can (and often do) have undetectable viral load. These people cannot transmit HIV to their sexual partners.

- You can’t get it from kissing. You can share straws. Even oral sex has extremely low likelyhood of transmission.

- Sex without a penis involved has basically zero risk of transmitting HIV.

- Medical care, even surgery, involving an HIV positive individual (either as a surgeon or a patient) is safe. This is true of dentistry too (dentists are safe, as are patients).

- Properly adhering to a PrEP regime reduces the risk of contracting HIV through sex by 99%.

- After exposure to HIV through sex or other means, PEP (which is somewhat different than PrEP, in that PEP is taken after sex, while PrEP is taken in advance of having sex) is likely highly effective at reducing the chance of contracting HIV (note it needs to be done within 72 hours after exposure, the sooner the better).

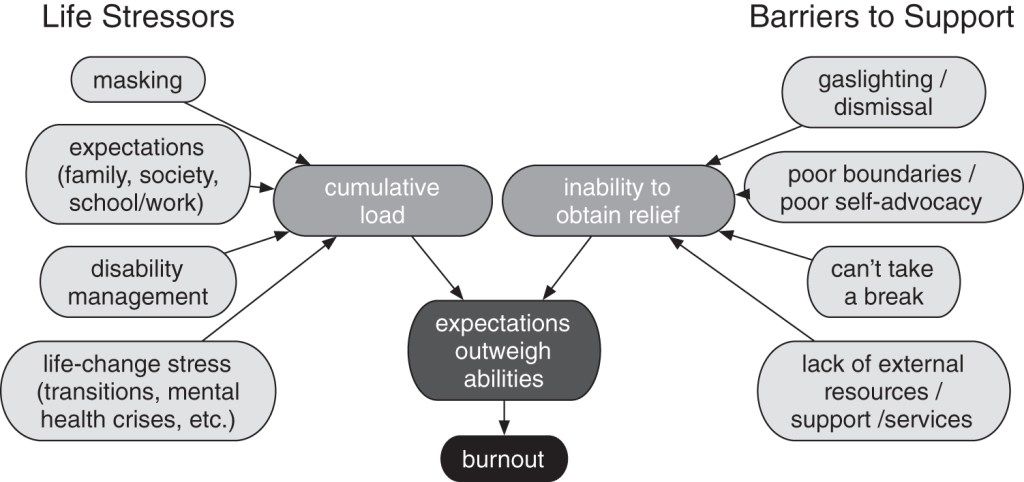

With this said, the idea that nearly half of trans women may have HIV still remains stigmatizing, and also causes public health focus to be directed broadly towards all trans women, when focus on specific risks might make more sense. I.E. targeting trans women in culturally-relevant ways who might be at low risk for HIV might be non-culturally-relevant to the subset of trans women who are at high risk of HIV. This means we need to stop treating trans women (or worse, trans people as a whole) as a monolith when it comes to HIV risk, and instead focus on subgroups within the trans women community in meaningful, appropriate, and proportionally-valid ways.

For instance, we know that only about half of trans women (between 44% and 58%, depending on their whether looking at people who desire vs. complete medical transition procedures, the two groups studied) in a Dutch study reported having had sex in the last 6 months. Clearly, people who are having little or no sex are less likely to have HIV than those who have sex frequently, particularly with multiple partners. While there are other ways to contract HIV than through consensual sex, it is clear that some groups of trans people are at higher risk than other groups.

But What is the Prevalence of HIV in US Trans People?

But, back to the first question, how common is HIV in trans women, as a group, even recognizing that some groups of trans people are far more likely to contract HIV than other groups?

Method 1: Calculating by Sampling HIV Positive People

We can sample HIV positive people, and determine how many are trans. If we divide the number of trans people by the sample size, we get a percentage:

Trans_Women / Sample_Size = PercentageThis percentage tells us what percent of HIV positive people are trans.

We know that in 2019, 1.7% (623 / 36,398) HIV diagnoses were transgender people, based on the National HIV Surveillance Report for 2019 (see Table 1a).

Let’s assume all these trans people are trans women (that’s almost certainly not the case, but stick with me). It’s quite possible this still undercounts trans women, but unfortunately it’s one of the better sources of data out there.

Next, we can figure out how many HIV positive trans women there are, total, if we know how many HIV positive people there are in the USA. Fortunately, we do have a good idea on this number. So it’s simply a matter of taking our 1.7% and multiplying that by the number of HIV positive people in the USA, which is estimated at 1.2 million.

.017 x 1,200,000 people with HIV= 20,400 peopleThis assumes that trans women always represented about 1.7% of HIV diagnoses, and that may not be a valid assumption, as we may have been less or more of any given years’ HIV diagnoses, but it’s likely a good ballpark. It should be noted that the number of people identifying as a trans women has been increasing over time, so, if anything, this rate may have tended to increase over time, causing this 20,400 to over-count trans women.

So…. Using this, we get an estimated 20,400 trans women in the USA are HIV positive.

The next step is to figure out the prevalence in trans women. This is fairly simple, at least in principle, using math — it’s a very simple formula:

H / N = Pwhere… H = Number of Trans Women with HIVand… N = Number of Trans Women (with and without HIV)and… P = Prevalence of HIV (1 = 100%, 0 = 0%)That is, we need to know two things — how many trans women have HIV (the numerator) and how many trans women there are total (with or without HIV) — the denominator. We have a guess at the numerator, 20,400 trans women have HIV in the US. So what is the denominator?

Unfortunately, we don’t know. Really!

But we can make some informed guesses.

Another Medium author, Melissa Ingle, wrote about how she determined how many trans people there are — determining that approximately .54% of people in the US are transgender, which matches other estimates. Of course not all of these trans people are women, so we will draw from the most recent CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data, which indicates that the likely population of “Transgender, male-to-female” people is .22% of the population (yes, I know this is problematic terminology, but it is the terminology the CDC used), which fits other scholarly estimates.

We know the population of the USA is roughly 328,000,000. So, multiplied by .22%, to determine the trans woman population, we find this is is 721,600 trans women in the United States.

So now we can calculate the prevalence, as described earlier:

H / N = PSo…. 20,400 / 721,600 = 2.8%Thus, based on this data, that approximately 1.7% of HIV positive people are trans women, we can determine that 2.8% of trans women are HIV positive. This is a far way off from 14%, 18%, 42%, or most of the other estimates of HIV positivity. Of course if the population of trans women isn’t 721,600, that could change this number (it may be higher or lower).

Method 2: Calculating by Sampling Trans Women

A second way of calculating this is to sample trans women, and determine how many of them have HIV — basically the opposite method from “method 1”, where we sampled HIV people to determine how many were trans.

Let’s look at one study, the one that is being reported as “42% of trans women are HIV positive.”

This, however, turns out to be difficult. There is no national registry of trans people, nor any organized system that captures a majority of trans people. Most studies that tried this method relied on sampling based on interpersonal networks of trans participants. For instance, the National HIV Behavioral Survey (NHBS) focused on trans women (the study that found 42% of trans women in their sample were HIV positive) by finding “seeds” or trans women in various cities, and asking them to recruit some trans women, who in turn recruited additional trans women. This “N-degrees of separation” approach to sampling isn’t going to capture a random sample of trans women, but rather will capture a sample of trans women that tend to have somewhat similar characteristics.

For instance, this NHBS study focused on 7 cities, representing some urban areas of the US. However, it’s possible, even likely, that HIV prevalence differs between urban centers, suburban locations, and rural areas. In comparison to other studies, such as the 2015 US Transgender Survey, which didn’t break out data by gender, but gave overall numbers for trans people, recent homelessness, poverty rate, and other demographics with associations with HIV positivity rate, we know the prevalence differed significantly between different subgroups.

There were other problems as well with the sampling in the NHBS, at least regarding calculating prevalence. It’s known that some trans women, after achieving a certain point in their transition (which may differ for different women) seemingly “disappear” from the trans community, instead preferring to blend in with the majority of women. These women likely wouldn’t be well connected to other trans people in the community, and not sampled by methods like this study’s sampling. Likewise, it likely wouldn’t count trans women who are living as men, and not known to the trans community, but whom identify as trans women despite living by appearances as a man.

The NHBS also relied extensively on incentives (small stipends) for recruitment, which would tend to recruit people that are more in need of the stipend, which might explain some of the high representation of people in poverty in the study.

Finally, the sexual activity of the study participants was significantly different than other studies. For instance, in the NHBS study, 76.7% of participants said they engaged in anal sex within the last 12 months (54.9% of the total sample reported not using a condom during anal sex). This number is high, and doesn’t reflect the sexual behavior of the trans population as a whole. A Dutch study on sexual behavior in trans people found approximately 50% of trans women reported they were not sexually active in the last 6 months — which would seemingly be incompatible with 76.7% of trans people having anal sex in the last 12 months! Indeed, many trans women are uninterested in using their penis in sex, and may be going out with another woman (trans or cis) who doesn’t have and/or use a penis, while others may engage in oral sex, play with toys, or other forms of non-anal, non-vaginal sex, which carry little to no risk of HIV transmission.

Basically, this study can’t draw conclusions about HIV prevalence rates overall. What it can show is to provide additional data and insights into some of the trans population, but it should not be used even to say that the rate of 44% is accurate even in big cities.

But of course these problems aren’t unique to this study. Most studies that attempt to sample the trans population have similar problems, as the definition of “transgender woman” can differ significantly between studies, often far more restrictive than the actual trans woman population, causing higher apparent positivity rates.

Other studies looked at testing of women who are far more likely to have HIV high-risk behavior than the overall population of trans women. Again, this would greatly inflate the positivity rates.

So, what percent of trans women have HIV?

I don’t know. I think the 3% number is a reasonable guess, although I wouldn’t be shocked if the number is somewhat higher — maybe 5–6% — as it is possible that trans women are under counted amongst people diagnosed with HIV (if only 1/2 of trans women were identified as transgender when diagnosed with HIV, then this number would be 6%).

What is certainly true is that it is not 42%! I also believe it’s likely not 28% or even 14%, although 14% is far more likely than 42%.

Indeed, if the prevalence was 42%, we would expect around 300,000 trans women with HIV. Recall that there are 1.2 million people with HIV in the USA, so 1 in 4 people with HIV would be trans women — yet as described under “method 1” above — the estimate we have is 1/15th that number (we estimate approximately 20,000 trans women have HIV using the most recent data we have for that). Likewise, if we assumed it was 14%, that would mean about 1 in 12 HIV diagnoses would be trans women, when the CDC’s data says it is about 1 in 58 — that’s quite the divergence.

So I’m sticking with my 3–6% number.

While I understand how an extremely shocking and high HIV prevalence figure can be useful for fundraising and grant writing purposes, it can also contribute to the stigma trans women face and can result in the focus of HIV prevention being turned towards the entire trans community when some parts of the community may differ in important ways from the rest of the community — and be best served by tailored messages and outreach that may differ from how you would reach the majority of the community.

What We Need Going Forward

We need good research. Good research is going to be expensive, time consuming, and difficult to conduct, because sampling the trans population (indeed, even obtaining good estimates of the size of the trans population, particularly from representative subtypes of trans people) is difficult. But we need that.

Specifically, we don’t know much about the following:

- How many trans women are there?

- How do trans women have sex? Surprisingly, this is answered only, at best, in limited studies that either focus on high-risk populations, are quantitative in nature, or involve only a subset of trans women (I.E. only women who have had bottom surgery within a certain area or at a certain institution). We need to know how prevalent higher risk sexual behaviors are, and what subgroups of trans women engage in those behaviors. It’s important we don’t treat trans women as a monolith in this data gathering.

- How many people getting diagnosed with HIV are trans? While we are now gathering and reporting on some of this data, there are gaps (as this essay points out) and we need to improve this data gathering.

- What about trans men and non-binary people?

- What HIV prevention messaging and methods are most effective for trans women?

Right now, the best guesses we have about HIV prevalence in trans women— and that’s really what mine and everyone else’s estimates are — are likely wrong. We need good data. Trans people deserve that.