This year [2022], at San Francisco Pride, organizers decided that cops can march in the parade, but not in uniform. That has, unsurprisingly, angered some, who point out that gay cops should be able to celebrate pride, accusations of non-inclusivity towards the Pride organizers, and condemnation by politicians who are scared of losing the vote of the people who displaced the queer community.

I’ll start by noting I’m not from SF, and so my opinion is of obvious limited value here. That said, I do know a bit about queer history, and I’m going to use the example of this Pride event to give my take on an issue that, sadly, we must revisit every damn year.

Origin of Pride — Police Violence

The first SF Pride events were a commemoration of two uprisings — one at Stonewall Inn in New York City and the other at Gene Compton’s Cafeteria in the Tenderloin of San Francisco.

Gene Compton’s Cafeteria in the Tenderloin was an all-night diner that was popular amongst the local residents — often trans women. Trans women were highly discriminated against, and frequent targets of police beatings, rape, and harassment. It was a place of community, to the chagrin of the owners who also discriminated against them. One night in 1966, the owners tried to kick them out, but the women stayed in the restaurant, while the cops were called. When the cops arrived, to carry out, through force of the state, discrimination and eviction, with physical force. When the trans people resisted, they were beat and arrested. This night was unusual, though, because trans people stood together and opposed this.

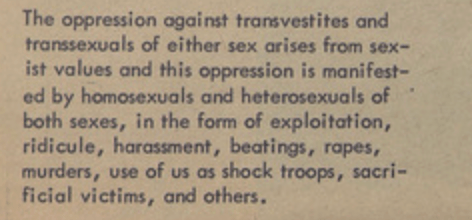

Of course this wasn’t the only time or place this happened, as police harassment nationwide. Trans women might be violating the law simply by wearing their clothes in public, and even if there were no cross-dressing laws in a given place, trans women were often harassed, beat, arrested, and even raped by police, because police knew that trans women had no resources or recourse to justice. Trans life also often intertwined with the underground economy, particularly sex work, as the corporate world wasn’t interested in hiring trans women. Indeed, until the last 15 years or so, it was generally impossible to be legitimately employed (except for the “lucky” few who could pass as cis women without being questioned). And those in the underground economy, particularly Black trans women, faced disproportionate violence from police.

Police also took the money of prostitution and bar owners who were breaking these unjust laws. Essentially, police in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district (and similar vice districts throughout the US) were running a side business off of these vices, profiting from it. And when they didn’t get their payoff, they would use violence to encourage future payment.

This was happening in New York City at the Stonewall Inn in 1967, where it was illegal to “cross-dress”. Police, in exchange for not busting the bar owner, the bar owner (via the mafia) paid the police to be left alone. Of course for whatever reason (perhaps they weren’t paid on time or perhaps they needed to maintain an impression of enforcing the law to placate people with more privilege), police still periodically arrived at Stonewall periodically, arrested people deemed dressing illegally (usually trans and lesbian women). Trans women of course were thrown into a holding cell with men at the local precinct, exposing them to violence from the men there. But in June of 1967, the gay prostitutes, lesbians, trans women, and others in Stonewall resisted.

The cops, while outside arresting queers, and expecting docile, obedient queers, instead found themselves facing a mob. The police ran into the Stonewall Inn and barricaded the door while they awaited reinforcements. While in there, the crowd literally tried to burn down the building — with the cops inside. This event is widely seen as the start of gay resistance, and the start of the modern gay rights movement (I’d contest that statement, but nonetheless it is widely held). Regardless, what happened is that in NYC and SF both, these events were commemorated with what was the first Pride events, which were a lot less corporate and a lot more militant, at least at first, than they are today.

Again, Pride literally is remembering standing up to police. That’s what we remember at Pride. That’s what we continue to do: standing up to those who oppress us.

So, frankly, I’m a bit confused why cops want to be at Pride in the first place, except perhaps to launder their reputation and history. That said, I suspect most gay cops would say that policing is different these days. It’s changed. So what happened since pride?

Elliott Blackstone — The Consequences of Being an Ally as a Cop

In San Francisco, a center was established for trans people to get all types of practical help, including identification that recognized their identity (albeit while also outing them as transsexual) and referrals to medical services. Astonishingly, these services were run in cooperation, at least on paper, with the San Francisco city government and the police force.

Sergeant Elliott Blackstone of the SF Police Department, was, starting in 1962, the official liaison with the “homophile” community in San Francisco. He was straight and cis, but also, by most accounts an ally, albeit an imperfect one, particularly when held to the standards of the modern times. But, unlike most of his fellow officers, he did not seemingly take bribes (while perhaps tolerating to some extent those who did) and lobbied for better treatment of queer people by the police.

In 1968, after the Compton and Stonewall uprisings, the National Transsexual Counseling Unit was established in San Francisco. This was a peer counseling organization (primarily focused on trans women) that, again, helped with the practicalities of trans existence. Sergeant Blackstone managed this unit as part of his job with the SFPD, in a strange and ironic twist of fate that put access to transition services literally in the hands of the police that were fought against a few years earlier. I will note that it was funded primarily by private donations from a wealthy Reed Erickson, a trans man, lest you think the police were being very generous.

Of course the police, by large, still harassed and brutalized trans people during this time. A police officer, acting under cover, convinced one of the peer counselors at the counseling unit to bring drugs to work. When she did, she was of course busted and this was used as a reason to shutter the counselling unit, cutting trans women in San Francisco off from services, likely the real goal of the officer busting the peer counselor. Blackstone himself also faced corruption from police, as cocaine was planted in his desk by other officers, to get a queer ally out of the force. That failed, but I’m sure Blackstone’s remaining few years in the SFPD was hell.

Literally, San Francisco police shut down one of the only legitimate ways to access transgender care that wasn’t via the underground economy. And tried to frame a cop who advocated on behalf of queer people.

But surely things have changed since the 1970s, right?

Gay & Trans Cops — And how the PD treats them

In 2020, Flint Paul, an SFPD Sergeant, and a trans man, settled his lawsuit against SFPD. He was harassed at work, including intentional misgendering, non-consensual disclosure of his trans status, etc, despite his very masculine appearance, putting him at potential risk. He received $150,000 in settlement for the pervasive work culture, although the city, again, denied responsibility in the settlement.

In 2022, Officer Brendan Mannix, a gay SFPD officer, received a $225,000 settlement for the way other police officers treated him at work. This included insults, harassment, and not providing backup that other officers would have received in dangerous situations. Literally, the SFPD officers put this gay officer’s life at risk. The city of course didn’t admit any fault, but they did pay out $225,000, and his prime harassers are mostly still employed with the SFPD.

This is not ancient history. It’s a continuation of a historical pattern. One which the SFPD has never fully taken responsibility for perpetrating.

This is also not unique to the SFPD. Nationwide, most trans cops resign shortly after transitioning due to abuse.

This is how “brothers in blue” are treated. Imagine how non-police are treated if they are willing discriminate in this way.

It’s fair to want real change

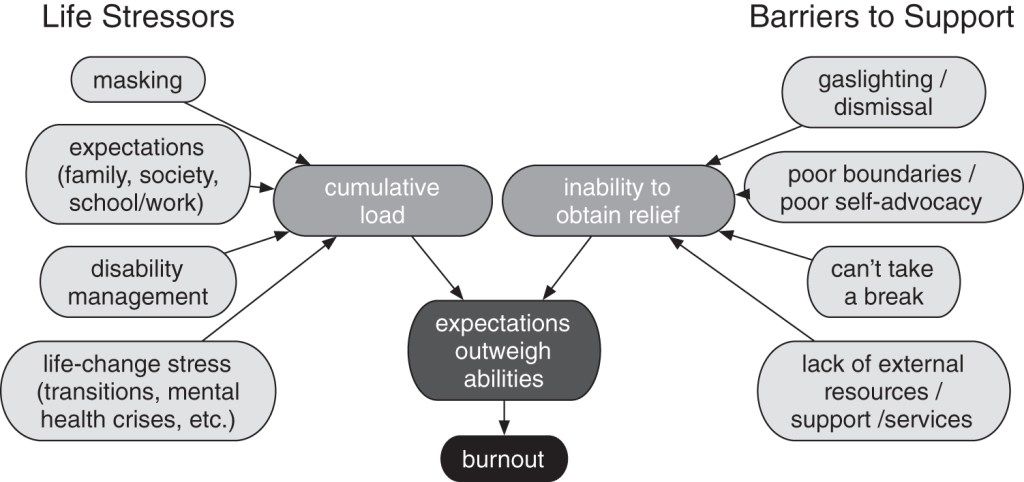

There’s a lot more I could say — I mostly talked about direct, interpersonal acts of discrimination and violence, but there are systemic aspects as well. Regardless, Pride is, in large part, a march against police violence. It’s fair to expect those who opposed you in the past to need to pass an extremely high bar before considering them friends, particularly while the carceral state continues to be an oppressive force in queer lives, even in spite of gay and trans cops being on the force.

Indeed, in another struggle, that against anti-Black police violence, there is good reason to believe that adding members of an oppressed group to the police force won’t solve the problem. The institution itself remains violent toward Black people, with or without better representation of Black officers on the force.

Likewise, remember Compton’s Cafeteria in the Tenderloin? The Cafeteria is long shuttered, but the building today is used as a halfway house run by a for-profit prison group, an example of the continuing impact of the carceral system that impacted the women in Compton’s Cafeteria on that August night in 1966.

So what now?

Apparently, SF Pride tried to compromise. When it comes to civil rights, compromise is nearly impossible, as it tends to anger both the oppressor and the oppressed. Indeed, that’s what it seems happened here. SF Pride said police officers can march, but not in uniform (although they can clearly indicate they are members of the PD, apparently). That hasn’t pleased a lot of LGBT people (particularly people who face intersectional oppression from the carceral state) nor the cops (or the police allies, such as the mayor) who, I guess, don’t want to be told what to do.

And it kicks off another round of people like myself weighing in on Pride. But just maybe we can reclaim a little bit of the substance of Pride without police there — and maybe even remember why Pride exists in the first place.

Pride started because of resistance to the police state. It might mean a lot more as well, but it can’t be separated from that resistance without losing its sense of place in history.