Once someone expresses a difference in public, others might realize that they, too, could express that difference, and that doing so might even improve their life, even though they’ll now be seen as different. For observers, this comes out of nowhere: suddenly this person has differences they didn’t have yesterday. What is up with that? Is it just people trying to be special and trendy?

Did you think I’m talking about gender? I’m not.

Photo by Allan Hermann licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

The photographer has no association with this blog.

So, what am I talking about?

I’m talking about disability. In this case, a disability that impacts my hearing.

If you’re a logical person, you’re thinking, “you can’t catch disability from hearing about someone else’s, certainly not something that impacts hearing!” You’re right of course, you can’t. But it still might look like it happens from someone looking in from the outside.

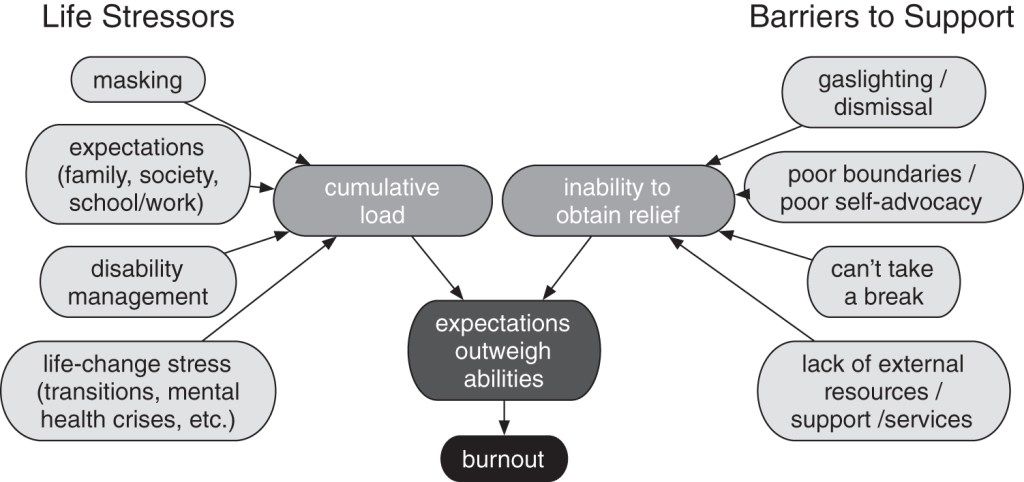

I’ve long struggled with an auditory processing disorder. I have trouble telling where sound is coming from, distinguishing pitches if the volume is also changing, and, most significantly, understanding speech (particularly if there is background noise). I mentioned this to coworkers, and that there was nothing that could be done because “I hear fine” when it comes to a “pure tone test” (that’s the kind of test you get in where you push a button or raise your hand when you hear different tones, although having done this recently, this also isn’t completely true for me, as my hearing has changed over the years). This is also overwhelming to me, because so many sounds make no sense, it’s exhausting to try to make sense of them. My problem is literally “in my head”, and not necessarily the ear. It’s the processing of sound—getting meaning from the sound, not the detection of the sound.

It turns out that there are treatments for this. I just didn’t know that.

One of the treatments I use is a combination of hearing aids with special programming (which can help make speech slightly more clear on their own) along with a remote microphone (this is particularly helpful in places like restaurants where I might want to hear another person, although I also use them in the classroom). While these things help, they aren’t perfect—there are still things I don’t understand that other people do. So I also use other tools when available, typically closed-captions, auto-captions, or CART (real-time captions). I use these tools in meetings, both in-person and remote.

Of course I had over four decades of pretending to hear things, and mentally guessing to fill in the blanks. With that much practice, I wasn’t bad at that, and few people would have picked up that I didn’t understand much of what they said. But now they might see me holding a microphone or an iPhone app that does captioning, or they might see me ask for CART at some events or meetings. So I went from “perfect hearing” to someone with, now, a visible disability through the use of assistive technology and services. This occurred over a short period, so it has surprised some coworkers.

Even more significantly, it came only after I mentioned my auditory processing disorder (which I knew I had) to a coworker, before I knew there were treatments. I mentioned, too, that there wasn’t anything that could be done. He disagreed and suggested (strongly) that I talk to an audiologist. If I hadn’t talked to him, I likely would still be guessing what people were saying, and still would look like I have normal hearing. From an outsider perspective, he gave me my disability.

That’s of course hogwash! One of the first times I used captions in an in-person meeting at work, I remember two managers at work coming up to me at and telling me that I made important contributions to the meeting. Of course I did: I could hear well enough that I could apply my experience in my field. Yet that didn’t typically happen before I started using the captions, because I simply didn’t understand the meeting!

So while it may look to some like I’m trying to be different or difficult, I’m now giving my full abilities to my employer and others (like my wife when we talk—if I ask her to repeat herself, she now asks me if I’m wearing my hearing aids, and more often than not when she does this, I’m not). The underlying disabilities was there even before I started using remote mics and captions and hearing aids. What changed was my presentation.

So I’m spreading this.

At a corporate event I recently attended, which had CART captions (which I requested), several people came up to me and told me how much the captions helped them. While some may have had normal hearing and just had difficulty with some accents or momentarily got distracted and could look up at a screen to see what was just said, others told me they had hearing loss but haven’t done anything about it. This wasn’t something they shared with everyone: I was safe because I visibility have difficulty, and, presumably, could understand how ableism can impact people’s willingness to seek help. If someone is wearing hearing aids, for instance, some might feel that shows they are too old, too incapable, or otherwise not able. Of course this is not the case, they are becoming badass cyborgs who can augment human limitations with the power of advanced technology, to perform at even higher levels than they already do (anyone hiding hearing loss is definitely performing at a high level!). They can have a better life. They might even prevent some cognitive decline by using hearing aids in the long term!

So of course I told them that they should talk to an audiologist, and suggested resources both available within my company and outside of it, and talked about how this has been life changing for me. Hopefully they will talk to professionals who might be able to help them.

Of course people who didn’t need this didn’t talk to me, and probably won’t be going to an audiologist too. It’s not contagious. Either you have issues hearing or you don’t.

But this is a Gender Blog!

I lied earlier when I said this wasn’t about gender. The example above clearly isn’t about gender, and it does reflect the experiences I’ve had with my audio processing disorder. But often trans people are accused of “suddenly” transitioning, because others don’t see the personal questioning and private reconsideration done, usually over years, before the person takes public steps. All they see is that this person is now demanding something new of them, much like I am when I ask someone to wear a remote microphone so I can hear them in a loud restaurant. They wonder why the trans person can’t just “take it slow,” similar to how someone might wonder why I can’t just listen like I did a few months ago in a restaurant. They don’t see that the person did take it slow, spending months, years, maybe decades getting to this point, nor do they see that a few months ago, I was just pretending to hear them.

They are essentially saying, “Sure, why can’t you go back to the old way? You know, the way where you participated less in life or were less happy?”

I know I won’t go back. And nor should anyone else.