Think about what makes something accessible. You probably think of ramps and elevators, and maybe you think of things like sensory needs. What about communication speed? Communication speed can be just as much of a barrier as a set of stairs, particularly for some autistic or neurodivergent folk.

What is Communication Speed?

I need to define my term. What do I mean by communication speed? Like everything around disability, it is complicated, and consists of multiple dimensions:

- Communication Method Mechanics – If I’m typing and you’re speaking, you probably can speak more words in less time than I can type (and I am fast, at over 100 WPM). Because I’m a fast touch-typist, if you use eye tracking or switches to select letters or words, you might write substantially slower than I do.

- Processing – If I’m talking about something I’m familiar with, I might be able to hear what someone says and process it, and, if applicable, respond quickly. But if they are talking about something I’m unfamiliar with and which ventures outside one of my scripts, I’m going to need a second to think about what was said and to process it. In the case of highly emotional stuff, it might take me days, weeks, months, or years!

- Interjection Speed – If I am part of a group that is having a lively discussion, I might need more time than another group member to sense the conversation has paused and that I can speak up. People with faster interjection speeds may (and often do!) begin speaking before I even realize there is a pause, and the conversation may move past the topic before I can speak up.

- Multitasking Speed – When someone else is speaking, can I think about my response? If I’m typing something, can I listen simultaneously to what someone else is saying, or is it one or the other thing? This too is part of communication speed!

- Communication Routing – The most direct way (route) to communicate about something isn’t necessarily the way we’ll speak. This can vary by circumstance for any of us, but some of us might have a route with more sightseeing along the communication route while we are saying what we want to say. This will slow down our communication. Others might be super direct, and get to the point quickly. Examples of routing are “autistic short-form” and “autistic long-form”, terms I believe were coined by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarashinha in the wonderful The Future is Disabled.

Different people are going to have different communication speeds, which can vary by communication situation (emotions and stress might change our speed of communication, as might sleep, topic of conversation, sensory input, and comfort/familiarity with our communication partner). Just as people may use AAC (Augmentative and Assistive Communication) or other alternatives to speech in some situations but not others (if this is unfamiliar to you, it is similar to the way some people use a wheelchair or other physical assistive technology in some situations but not others), our communication speeds can vary just as part-time AAC users may vary in their ability to speak words.

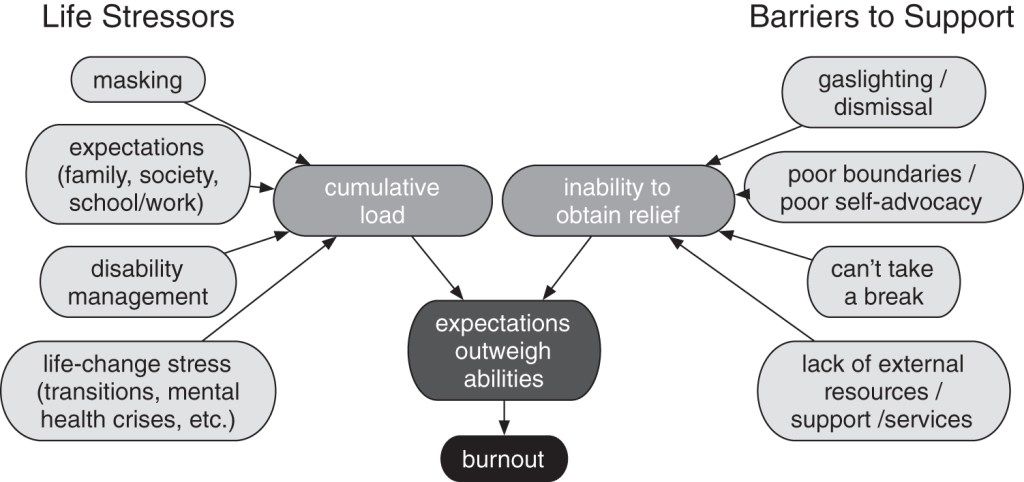

If there is a speed mismatch, this causes a problem. It can mean one person in a group is commenting about something from 15 minutes ago that everyone else has forgotten about. It can mean that someone is getting their voice heard, while another person is struggling to say anything. If we care about people, if we care about communication, we need to pay attention to communication speed mismatches. This isn’t just about neurodivergent people, either–there is often someone in any random group who tends to speak more than others, but they aren’t necessarily the person with the most to say!

Solutions

So what do we do? The answer is surprisingly simple: We need to slow down and make sure everyone has a chance to speak up. This can take a lot of forms. It might mean slowing down our interjection speed for someone taking us on a scenic communication route, so that they can actually take us to their destination. Some people may be more sensitive to interruptions than others, and may be shut down by an interruption. Regardless, we need an anti-capitalist approach because capitalism often prioritizes speed and productivity over actual communication. Thus, any solution might feel a bit awkward to us, as many of us are used to the productivity-focus of capitalism. But we can slow down (before my ADHD friends speak up, please read to the end of this post–follow my whole route, because I do likely address to your objection)!

So how do we remove the communication speed barrier?

- In online discussions, we can build systems with rate limiting built-in. One system I participated in had a limit of 3 messages per participant per day. Sure, communication moved a lot slower. But people in different time zones, people with slower communication modalities, people for whom processing was slower, people with limited energy, and people with a crisis in their lives had an equal shot at being heard.

- Normalize people being able to indicate they have something to say. Sometimes timing interjections is hard! One thing we do in the Colorado Trans+Autistic Peer Support Group is to allow people to use the “raise hand” feature in Zoom. You don’t have to do this (for some people this too can create a barrier, particularly if they’ve faced abuse for speaking up or taking up space). If you don’t want to use that feature, that’s fine, but you are asked to wait about 3 seconds after the other person finishes talking (this prevents interrupting a scenic route when the person hasn’t fully taken us to the destination yet, or when someone has non-typical pauses in their communication that might be mistaken for being finished). If someone has a hand up, they have priority. This lets people who have a hard time interjecting have a way of saying, “I want to talk!”

- If someone is typing in response to others speaking, it is often best if the system they use indicates they are typing, so people can wait until moving onto something else. If you have mixed groups of typers and speakers, you might also want to ask the typers if they want quiet until they are able to get their thought out–and certainly you probably don’t want to just move on to another topic until they say what is relevant! Of course everyone is different, so different people will have different preferences. That said, disabled people are taught, both formally and informally, to put others’ comfort above their own needs, so you will need to build trust between communication partners. Make it clear people can try different things and change their mind, and that’s okay to do!

- Intentionally privilege the people with the slowest communication speed. If someone has a slow processing time and/or slow interjection speed, they might not speak up much in a group. So consider pausing and giving them time to process before moving on. In a group where some people type and others speak, you might read out the typed messages before anyone else is allowed to interject, to give priority to the typer (in particular, the speaker can likely remind us what they are replying to, but if 5 speakers all talk about something rapid-fire before the text is read, the text might not make sense anymore).

But…What About Conflicting Access Needs?!

But, wait, I can hear my fellow ADHD-ers (and others!) speaking up–“I don’t want to forget what I’m going to say” or “I can’t concentrate if things are moving too slow.”

This is a legitimate access need, too. But the solution to conflicting access needs isn’t to throw up our hands and say, “Shoot, we can’t do anything about this, so let’s not! Conflicting needs!” It’s to negotiate and find a workable solution.

There are two principles here: First, it’s not appropriate to ask someone else to do all the work, and second, different people may have more or less difficulty adapting. For instance, it probably is difficult or impossible for a typer to communicate as fast as most speakers. They are probably already putting in a ton of effort to type as quickly as possible! So if they are putting in effort, what can someone who will lose their chain of thought do? Are there adaptations they can do? Perhaps they can write on a post-it or a memo application that they want to respond to point X, while the typer is composing their thought. Then, once the typer has conveyed their thought, they can refer to the note and speak up. Of course notes and memo apps won’t work in every example (this probably won’t work when you’re swimming together in the ocean, and might not work for sexy time with a partner!). But what can you do? If you know you have a need for things to move fast, you can either choose to exclude the communication of people who are slower or you can find assistive technology and adaptive techniques to convert between baud rates. I hope most people don’t want to exclude the slower communicator (they are probably excluded far more than the fast communicator is!).

So you negotiate. What can I do? What can they do? Where do the circles overlap? Is there a part of that overlap that is more equitable than other parts, as far as effort expended? Hint: There is almost always overlap. If you watch anything on Tik Tok or read an article on anything or view a graphic novel or watch a TV show, you are engaging in a form of communication that is slow but doesn’t feel as slow as it is. The difference in time between when the words were conceived and the time when you hear/see and process them is likely days, weeks, years, maybe centuries! When you come up with a strategy for a group (or a pair of people), everyone will need some openness to the reality that we can’t always have what is ideal for us when interacting with others if we want to optimize communication (and not just our own communication style/needs). For instance, maybe an interactive discord isn’t the right choice, because the fast-processor and the slower communicator won’t be able to get their baud rates in-sync because the communication mismatch is too great. But maybe they could write email to each other (and maybe not, but that’s the point–it might take a bunch of investigation to find the appropriate way of communicating, and in a group it might look different). Look for alternative ways to communicate that meet everyone’s needs–theirs and yours.

Making a Better World

We can learn a bit from successful open source projects, as well. Sometimes there is no need in open source for a lot of communication communication–the entirety of the project might be one person. But often there is a need for good communication, and it crosses language barriers, time zones, work schedules, religious calendars, and communication modalities. A lot of open source projects will use a proposal format where a change or improvement or problem is mentioned, and people have some time to respond to it. That’s a way of slowing down communication, recognizing that getting many viewpoints is important. What can be done for in-person gatherings? Zoom calls? Discords?

Is there a solution to let everyone participate in every group equally? No, of course not. But, that’s the wrong question. We should be asking, instead, “How can we make communication in this group work for everyone?”