A note: This talks about self-harm and bullying.

It was the last day of elementary school, and I was in the principal’s office. Was I not going to be allowed to graduate elementary school?

But lets take a step back, and see how I got there. When I went to school, elementary students would do the “Presidential Physical Fitness Test”. It involved things like pull ups (for people assumed to be boys; for people assumed to be girls, it was a flexed arm hang), sit-and-reach, shuttle run, sit-ups, and 600m run/walk. For each age, there was a standard that if you met, you would get some sort of award. I wouldn’t know much about that.

I was the least athletic kid in my 500 kid elementary school, and am still fairly uncoordinated. I was the kid who was too uncoordinated to walk the balance beam or throw a football (something I still can’t do). I have never caught a ball in a friendly game of anything (even as an adult). Dodge ball was my nemesis. I still don’t know how people can climb a rope, and I don’t believe I’ve ever done a pull-up. I was the last kid in class picked for anything. When I did learn how to do something, it took years longer than my classmates-when they were riding a bike without training wheels in kindergarten, mine stayed on years longer. It didn’t help that when I entered 7th grade, I weighed less than 50 pounds (< 23kg). I was a scrawny, small, uncoordinated weakling.

As our current Dear Leader in America (well, Trump) is wanting to re-instate the fitness test–after all, we need to be ready to send teenagers to war to die for their country’s politics (one of the primary stated purposes of both the original version of this test and the current one is “military readiness”)–I think back on all of this, and how humiliating it was to consistently be the worst kid in PE class on every part of this fitness test. It wasn’t motivating, it instead caused me to hate PE.

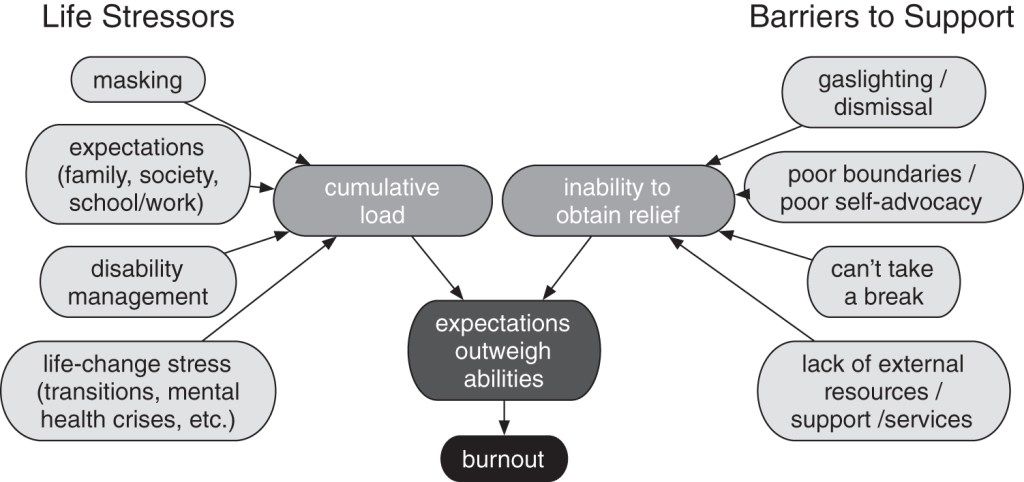

It wasn’t lack of effort on my part. I spent most of every day during the summers, and almost every evening, doing things outside. I loved exploring my city and the surrounding area, and I climbed trees, explored the city’s storm drain system, walked and cycled miles from home, and a bunch of other solitary pursuits during elementary school. I may not have been the most active kid in my neighborhood, but I definitely wasn’t the least active. Yet still, I was weak. I look back and know part of the mystery: I’m dyspraxic, something that is common among autistic+ADHD folk. I didn’t learn that until I was an adult. I still don’t know why, despite a lot of effort, I can’t build upper body strength (a while ago, I did several years of weight training three days a week, never gaining any strength in my upper body, although my lower body did gain strength).

The school, where I was doing these horrific Presidential Fitness Tests, may or may not have known that I was dyspraxic, but they knew something was up. I received adaptive PE for the last few years of elementary school. They had words and labels for me, I’m sure. But one thing that didn’t happen was to tell me the labels. Never was the word disability used. That was a problem.

Tests like the Presidential Fitness Test instill an idea that if you work hard, you’ll be able to pass the test. While hard work might enable some to clear the bar (or do a pull-up), that didn’t work for me. It doesn’t work for a lot of kids. But if this idea of “if you work hard, you can do it,” is internalized, as it was in me, that can lead to a pretty horrible view of your efforts when you can’t do it. I thought I wasn’t trying hard enough. I now know I was trying way harder than most of my classmates. But it angers me that I didn’t know that as a kid. Adults knew something was up, and if I knew I was dyspraxic (and/or autistic), and that was presented in a child-friendly way, I could have learned alternative strategies and learned to judge success by progress rather than an arbitrary number I could never meet. For a bullied kid, who never understood that other kids were seeing my autism and dyspraxia–and that was their problem, it could have been life giving. As it was, I tried to kill myself, in elementary school. And the labels the other kids had weren’t autism or dyspraxia. It was f*****t (an anti-gay slur, because of the way my body carries itself) and r****d (a horrific slur for people with intellectual disability, with whom I was lumped in with due to social differences and, again, the way I carried my body). Fortunately I was incredibly bad at killing myself, too.

I understand the idea adults often have that if they “give” a child a label, that forecloses possibilities, it limits a child’s future. But it doesn’t have to. There are ways to explain labels, and ways to advocate for a child, that both respect a child’s differences (including their difficulties) and gives them more possibilities.

The alternative isn’t a future with no labels, either. Holding back the label that accurately helps the child understand who they are just results in other labels being applied to the child, both by the child themself and by others in the child’s life. For me, lazy, f****t, and r****d. Those labels are limiting too.

I wonder what would have happened if an adult in my life were able to tell me I was autistic? I imagine the conversation could have went like this:

“You’re brain is different than most people’s brains. That’s okay! People like you are called ‘autistic’. No, not ‘artistic’, ‘autistic’. But most people are not autistic. That means they won’t always understand what you are doing or why you are doing it. And you might not understand what they are doing. It might make it harder for you to be friends with some people, and some people think it is okay to be mean to autistic people, but that’s not okay. Some things are harder for you. I noticed you have trouble catching a ball, and that is something some people with autism have trouble with. You will always be autistic, and that is okay! It isn’t bad to be autistic. But also we know how to help autistic people be happier, because autistic people who grew up taught us what makes them happy!”

Sure, it would be more interactive, but it can be simple, acknowledge the real difficulties and differences, provide opportunities for future discussion. I would tell parents to seek out a diagnosis and tell their child about their diagnosis, not so you can fix the child (autism can’t be “fixed”), but so that the child knows that they aren’t morally broken or lazy. They are probably working really hard. They need to know they are working hard, and knowing that their difference has a name and what that difference means can help them understand that even if they can’t do something as well as another kid, it doesn’t mean they are morally bad.

But back to my proudest day, in that principal’s office. I was terrified I wasn’t going to graduate. Shortly before my trip to the principal, I was in a school assembly, with all the other kids in school, and our PE teacher gave all of us 6th graders our fitness test records. Mine told me I had the worst shuttle run and 600m run in the school (well, they didn’t say that, they just listed horrific times). That I couldn’t do a pull up. That I could do only a fraction of the number of sit-ups that would be “good” to do. It was a record of my moral failure, of my supposed laziness.

Somehow, something in me knew what I could do. I don’t know what did it, because I usually tried really hard to get adult approval, but I tore up my records, and made a bit of a pile of the paper. Several other kids, other unathletic kids (although more athletic than me!) did the same, and we had a reasonably sized pile when done. The PE teacher was not happy about that. So we went to the principal.

The principal never did anything to us, we just sat in his office until the end of the day, which was fine. But it sure would have been nice if I knew why I was so bad at athletics and if I didn’t have a record of it, but rather was taught in PE about ways I could be active that didn’t measure me against an impossible (for me) standard. But looking back as an adult, I am really proud of the young Joelle who tore up her record of failure. I’m also glad that somehow she could see a bit of the injustice done to her as injustice and not her own failure, even if it was in a more limited way than she can see now.