Me: “We need to leave. Now.”

Him: “Huh?”

Me: “Just…let’s go. Really.”

Him: “What?”

Me: <exasperated whisper> “Don’t you see the way I’m being looked at? We need to leave.”

Him: “Nobody is looking at you!”

Me: <annoyed whisper> “Yes they are, and I’m going to leave without you if you don’t come with me.”

I’m a trans woman. He’s a cis man. But I bet many of my readers have been on one side of this conversation–and likely both sides–at some point in their lives, regardless of their gender history. Maybe it wasn’t about gender, but about skin color, the language being spoken, religious dress, disability, class, or else entirely. One person knows something is wrong, the other can’t see it.

It’s related to a film trope–there’s a bar, there’s some music playing, but when the protagonist walks in, the needle scratches and the record stops. You know something bad is about to happen. It is usually a lot more obvious that someone is out of place. It is them versus the bar.

Here’s one of my favorites:

Let’s think about this scene a bit though, at least the opening, as it doesn’t end like it might in real life.

Vinny is clearly out of place in this bar. He’s about to get his ass kicked, with the film playing up the redneck-vs-city-slicker trope. But rewind a bit more, to what was happening before Vinny walked into the bar–what was happening then? A bunch of people, most of whom probably friends, were hanging out at their local bar, joking around, maybe hitting on someone of the preferred gender, and, yes, drinking. If you asked any of them to describe their nighttime hangout, how would they describe it? Friendly? Down-to-earth? Welcoming? Fun? Ya, probably these and a bunch of other things.

Now think of someone like Vinny, but perhaps not as quick-witted. This person walks in. What do they experience? It’s probably not the same thing.

Who is right?

Maybe both are.

This is a common trans experience. I’ll hear a friend describe flying an airline known for luxury–and what an experience it was. He might tell me about how fancy the plane was, how the first class passengers even have private rooms! He then says, “You should fly them sometime!”

Of course I then remind him that the airline’s hub is in a country where it is illegal to be trans, and where western trans women have been detained and refused entry, and that I have no desire to find out if that would happen to me, regardless of how amazing the airline might otherwise be. I’d prefer being stuck on the airport ramp in a Spirit Airlines jet for seven hours! I mean, I’m not one that is upset about experiencing some luxury, but I’d prefer to have to pay extra for a bottle of water and some crackers than to risk jail.

Why would my friend, who knows I’m trans, even suggest I risk this? It’s simple: it didn’t even occur to him that my experience could be significantly different than mine. He, no doubt, had a wonderful experience.

Even more significant: the response of people like my friend in this situation is often, “Oh, that wouldn’t happen to you!” Maybe they are right, maybe nothing bad would happen. Maybe I’d have a great time. But if they are wrong, what happens to them? Not much. What happens to me if I get this wrong? I end up in a jail cell in Dubai. We are not the same.

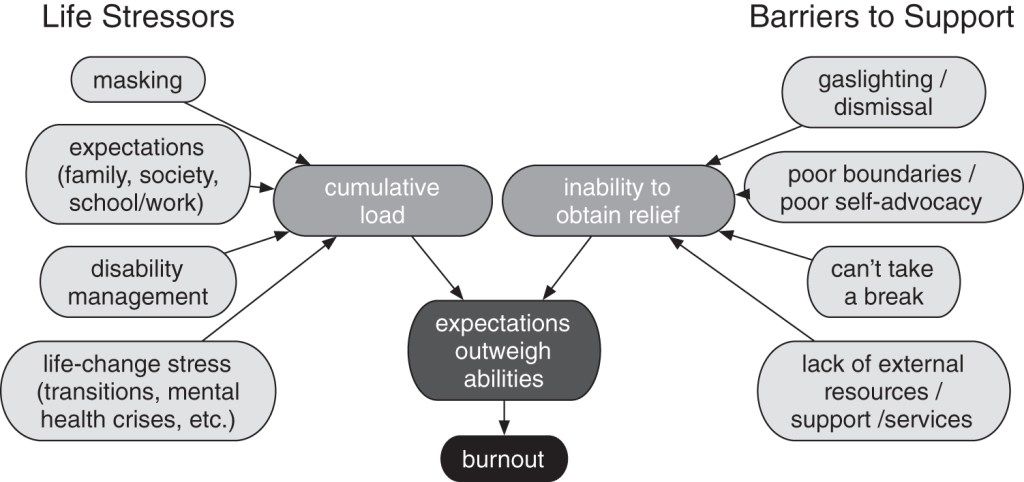

Because of this unequal consequences for being wrong, marginalized people often develop a sixth sense. I’m used to entering a space and looking around: are there other queer people here? That might be a sign that the place at least tolerates people like me. Or do I see a guy that might be a little too drunk wearing a “There are ONLY TWO Sexes” t-shirt? A cis friend with me probably won’t notice either person, but I will. That’s because her life doesn’t probably depend on getting this right, while mine does. I’m looking to see if the Jukebox is playing “Born This Way” or if the record skips.

Of course sometimes I might not even know what I’m seeing, just that something doesn’t feel right. I can’t explain it logically. Maybe I’m wrong, maybe I’m right, but I’m probably not going to stick around to find out. But, unless my friend is trans, even if they are close to me, they probably won’t understand.

Other times, I look around and I do know what I see–and I know I need to leave. I see something that immediately signals danger–but the signal might not be visible to everyone. Maybe I see someone with an “88” tattooed on their arm. I mention it to a friend, and she just says that it’s probably his favorite football player. It’s just a number after all, but I see it and know that white supremacists and Nazis–two overlapping groups that typically also hate trans people–also love the number 88. That’s a dog whistle: a Nazi seeing someone with “88” tattooed on them will know that person is probably like them. They’ll recognize it. So will a lot of marginalized people targeted by Nazis. And while this is more widely known than most dog whistles (the name comes from the idea of a dog whistle which a dog can hear but others cannot), so it’s more likely to be recognized than a lot of dog whistles, there are still a lot of people who won’t have any idea that a two digit number signifies anything particularly sinister.

But it’s not usually outright Nazis and proud white supremacists I’m avoiding. It’s respectable people that might make my life difficult. The phrases they use might even sound good. Someone might talk about how they believe in “protecting children.” Who doesn’t want to protect children? That’s a good thing! But it’s also been co-opted by transphobic and homophobic people who see gay and trans people as a danger to children. But if my friend isn’t aware of how “protecting children” has been weaponized against trans people, they might not understand my concern when someone talks about how our number one priority should be protecting children from being sexualized. They might be thinking about children that are sexually assaulted, something everyone should agree needs to be stopped. They might not be thinking that a lot of people using this language want to prevent trans people from being visible in public. Any reaction I have to this phrase, in the eyes of my friend, will be an overreaction.

This isn’t just about places like a bar. Marginalized people look for these things in every place and community we might be part of. If a job ad tells me that the company has a “strong commitment to family values,” I ask myself, “Why did they phrase it that way?” After all, I know “family values” doesn’t just mean being present for children and caring about their well-being. I know it’s weaponized to mean privileging heterosexual married couples as the head of the family, above other types of families and relationships. Maybe the employer doesn’t mean it. But do I want to bother applying to find out? After all, what if the employer does mean that?

I might sense a place is accepting. I might see not dog whistles, but subtle signs of acceptance. Maybe I walk into the bar and the bartender has a rainbow flag pin, or I see two another trans person laughing with her friends. Instead of gendered bathrooms, I see two doors in the hall with just labeled “toilet” without any gender labels. Do these things mean the place is safe? Of course not, just as seeing a dog whistle doesn’t prove it is dangerous. But it’s a signification that weighs in the direction that it may be. Likewise, take that job ad again. Let’s say I see a job ad that explicitly mentions family planning benefits. I’m not going to need these benefits myself, but it also tells me that the company is not likely governed by extreme right-wing principles, which often also include discrimination towards trans people. Does it mean the job will be great for a trans person? Again, of course not. But it is a sign that points in the right direction.

But all of this might look like I’m reading too much into things to my friend. Does a rainbow flag pin actually mean anything? And I’m not in need of family planning benefits. Am I making too much of this? Maybe, but I know that that some people wouldn’t wear a rainbow pin or offer family planning benefits. Sure, plenty of people don’t wear rainbow pins but support queer people! But you don’t see many Nazis wearing them either.

But still, my friend doesn’t understand. You see, he can select his international airline based on the luxury experience the airline offers. I cannot. These are entirely different ways of evaluating the world.

More so, think back to the bar my friend likes. The one he describes as fun and lively–and for him it is. When I say that I don’t feel safe here, he knows he’s always felt safe. Who is right? Again, we both can be. He might be safe, and I might not be. But it’s his favorite bar, and he knows it is safe. He might even be defensive about it–after all, this is where he goes with his friends, and they’re decent people! But he just doesn’t see it. It’s not safe for me.

What can my friend do? What if you are that friend? Respect me. Respect marginalized people when they tell you about their experience, and realize they see things you do not. A marginalized person might hear the dog whistle you think is just a nice statement in support of families. They might know why “all lives matter” isn’t the positive statement it seems to be in a literal reading. Maybe they can explain why. Maybe they can’t, maybe it’s just sixth sense. Either way, if you respect them, respect that they have experiences and understanding you might not have. When a marginalized person points out a problem with your advertising, and can’t explain it, maybe it is time to engage experts. When your church posts “we welcome all” but no queer people seem to attend, maybe find out how that is used by other churches to mask a church that supposedly welcomes everyone, but then teaches that their existence is sin. Maybe ask marginalized people how they can make a place more welcoming to people like them. And you know what? You don’t need to ask me or your marginalized friend, employee, or church member this. You can do your own research (and, if you’re a company or a church, you can hire experts who specialize in this).

But what you shouldn’t do is tell me I’m wrong. For you, this might be an intellectual argument. For me, it might be my life.